To calculate which restaurant in Athens has served the most meals to the most diners, we would likely have to engage in a research project worthy of 10 University of Georgia doctorates. Any rough guess would include long-running franchise locations like Red Lobster or the McDonald’s on Prince Avenue. The recently-closed Mayflower, in business for seven decades, would make the list, as would a few other long-standing favorites like the Taco Stand, Strickland’s, Wilson’s, Add Drug’s lunch counter, Tony’s, and Poss’ Barbeque.

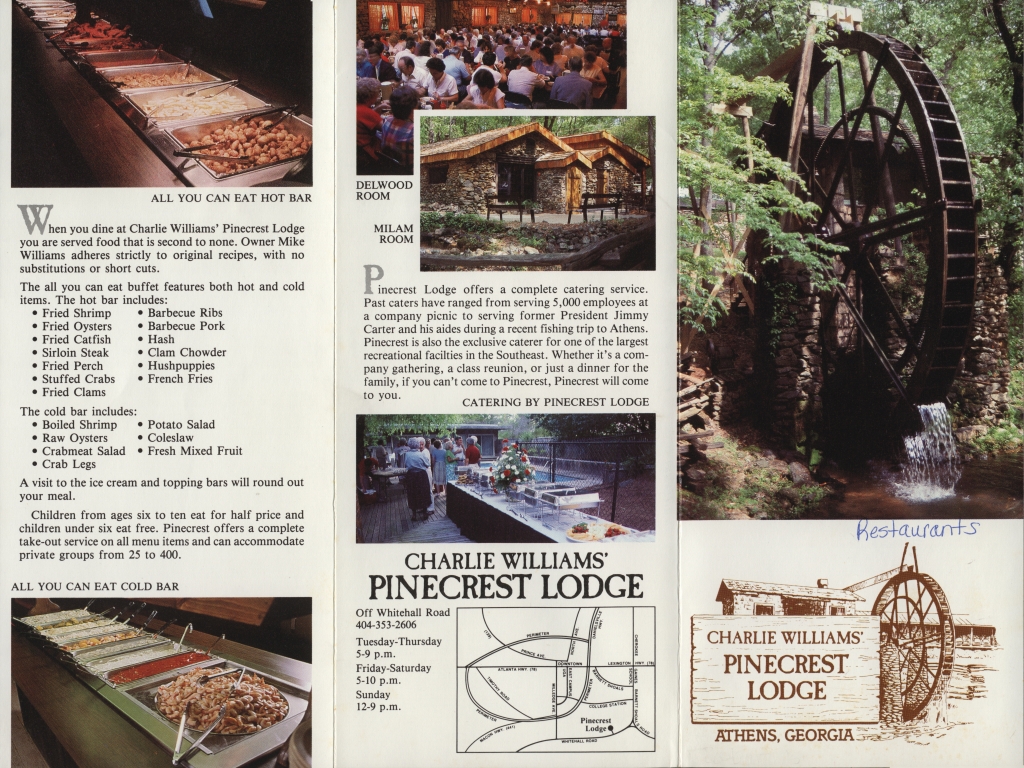

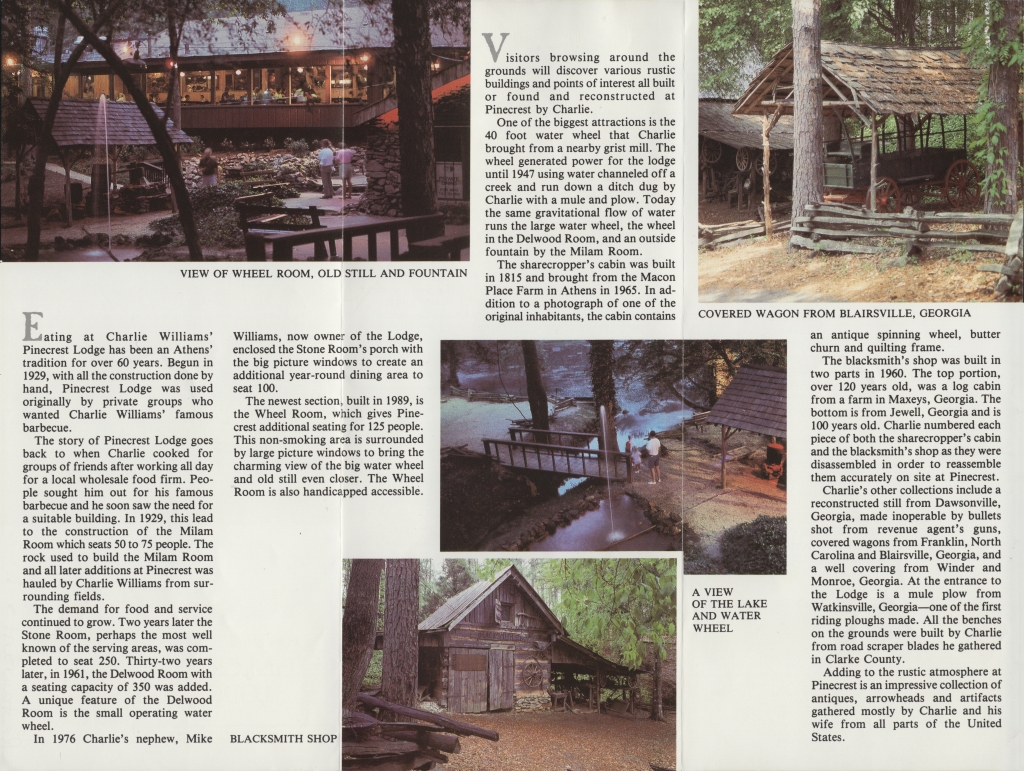

Standing tall among those local legends would be Charlie Williams’ Pinecrest Lodge, not only a restaurant but also an event venue and historical site. Located off Whitehall Road, the Lodge occupied a large plot of land with a lake, multiple buildings, and other features, such as a water wheel that came from the old Puryear textile mill, creating a relaxing rural setting. It was in business from 1929 to 2004, a time span that saw the restaurant’s clientele increasingly appreciate it as a welcoming refuge from the growing city that surrounded it.

Only in the last three decades of that span did Charlie Williams’ operate as a restaurant regularly open to the general public. It was originally a dining and party venue available by reservation, mostly rented by University-related organizations. In either phase of its history, it was loved for the food it served, including barbecue, fried fish, hush puppies, and other Southeastern staples.

Recently, Historic Athens added what remains of the Pinecrest Lodge to its Places in Peril list. Since 2019, this list has enabled that organization, and local citizens interested in historic preservation, to focus their attention on structures that face demolition, fatal decay, or significant redevelopment. Though another restaurant, Rass ‘n’ Ruby’s, took the Lodge’s place on its historic property for a few years, by the end of the 2000s the buildings were unoccupied and beginning their decline, with the exception of one building adjacent to the water wheel, until recently rented out as a private residence.

As with most of our articles at the Heritage Room’s Athens: In Time blog, we begin the research process with old newspapers; given the Pinecrest Lodge’s University connections, the student newspaper the Red and Black most of all. The most frequent mentions of the restaurant that we find in the digitized Red and Black came in the paper’s society pages. Columns like “Social Briefs,” “Campus Capers,” and “Social Spin” from the 1940s through the mid-1960s let fellow students know about the parties taking place every weekend. Charlie Williams’ is mentioned regularly, with parties booked many Friday and Saturday nights. One example comes from December 5th, 1941, two days before the Pearl Harbor attack: a notice about a fraternity barbecue party taking place that day. Another example, a notice about a sorority hayride on January 10th, 1947, lists attendees (“actives and pledges”) and their dates. On the same page of the paper’s March 7th, 1952, edition, both a fraternity “shrimp supper and dance” and the Economics Society’s social are announced, apparently taking place at the Lodge on the same night. Which would you rather attend? The Lodge also became well-known in both phases of its history for welcoming the University football team, both before and after the “big game.”

No surprise, the restaurant also consistently advertised in the student newspaper. Below are examples of the ads run by the Lodge plus one run by Alpha Chi Omega for a “dance and crowning of Mr. Apollo.”

The parties held at the Lodge often featured live music. Indeed, the Lodge joined the fraternities themselves, located on Milledge Avenue, in being a crucial part of Athens’ music history. Before the 1970s–especially due to the strictures of racial segregation–the opportunities to see live music in formal settings in a small city like Athens were limited. The Last Resort opened in the later half of the 1960s and some restaurants featured music performances to entice customers. But in the 1950s and early ’60s, if you wanted to hear the rhythm-and-blues and rock-and-roll sounds that were dramatically changing American society, you had to go to private functions, fraternity parties most of all.

Local resident Chris Jones has been engaged in research on this topic for several years now, offering Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI) classes and writing an article for BoomAthens, “White Fraternities and Black Music in the Early ’60s.” Both the Red and Black and his original research show that the artists who played at Charlie Williams’ included Brook Benton, Bobby “Blue” Bland, and none other than James Brown, one of the most influential performers and recording artists of the twentieth century. Brown, in fact, played multiple times in Athens during these years, sometimes with his own groups and other times with local acts like the Blues Benders backing him, almost entirely at fraternity parties, but culminating triumphantly in a concert for 8,000 attendees at the University Coliseum on May 7th, 1966, during Greek Week. (A charming artifact of this event comes from the Athens location of Miller’s department stores letting potential customers know they could buy Brown albums, as well as those of Dionne Warwick, who had played the Homecoming Concert the previous fall.)

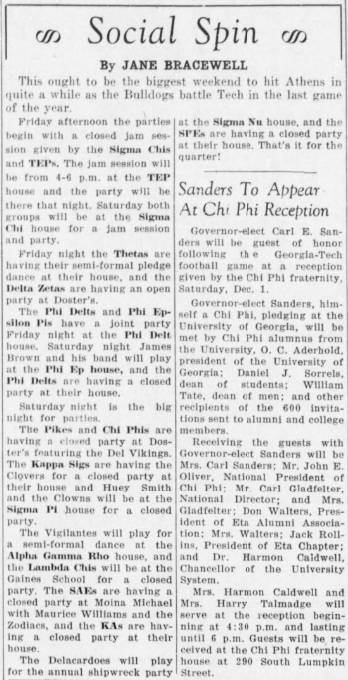

Examples of these concerts mentioned in the Red and Black society pages follow. The column from November 14th, 1963, notes appearances by Brown, the Fiestas, Dee Clark, Booker T and the MG’s, and a performance by local favorites the Embers alongside the amazing double billing of Bobby Marchand and John Lee Hooker. No wonder the columnist states, “This ought to the biggest weekend yet in Athens.” As Chris Jones’s article notes, 1963 had already witnessed an impressive selection of artists playing for Greek Week.

The “Social Spin” from a year earlier mentions yet another James Brown performance, as well as appearances by Huey “Piano” Smith and His Clowns, Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs, and the Clovers.

To provide additional context, check out an Anderson Independent-Mail article by Vince Jackson discussing James Brown’s performances at a small Clemson club: with segregation still the law of the land, artists like Brown performed at smaller “chitlin’ circuit” clubs for black audiences, larger venues and college-related functions for whites.

As noted in the BoomAthens article, however, those university-related events in Athens were not officially sanctioned and did not take place on campus. University officials, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, resisted integration. They were taking their cues from the state government’s efforts to stop Georgia teams from participating in integrated sporting events. The Interfraternity Council and the Student Council worked to overturn the policy. Court decisions, soon enough, resolved the situation. While events at the Lodge were not open to the public, some of the fraternity parties that featured live music happened outdoors and drew a great deal of attention. In addition to frat houses and the Pinecrest Lodge, some events noted in the Red and Black took place at the Wagon Wheel Supper Club. Similar concerts were happening at the Moina Michael Auditorium, located on the Atlanta Highway where the Heyward Allen car dealership is now. Some of the local bands that played these parties would go on to other musical endeavors. For example, the Jesters, via connections established by playing at fraternities, would go on to play in Myrtle Beach, backing up singers like Marvin Gaye at Cecil Corbett’s famous Beach Club.

—

In recent years, a great deal of attention from both local-history buffs and cinema aficionados has been directed toward Poor Pretty Eddie, which was, until recently, one of the few feature-length movies made in Athens, much of it filmed, to be exact, on the Pinecrest property. An exploitation film, but with an all-star cast, the financial backers of which clearly hoped would be another Deliverance, it never quite found its audience until retrospective interest in 1970s American cinema finally inspired viewers to take a second look. Among the many articles written about this film are local reporter Andrew Shearer‘s overview of its development and reception; a piece explaining why it is not one of the 366 weirdest movies ever made (maybe it’s no. 367); critical analyses by Foster Dickson and Elizabeth Erwin; a thorough study by Chris Poggiali that includes several stills, not least of the Lodge; and, finally, an essay about Athenians’ uneasy relationship with the film, written for Flagpole by Donald Shelnutt.

Live concerts continued to take place in the 1970s. In 1972, a local booking agency called Pedestal Productions put on a “Rock ‘n’ Roll Bonanza.” The Red and Black advertisement for it is below. The short-lived Pedestal also put on at least one show at the J & J Center, headlined by Ravenstone, recognized now as pioneers of live rock music in Athens.

Though concerts and large parties became rarer after the Lodge switched to being more of a regular restaurant, three decades later, in April, 2002, the Jesters played one of their later shows at the restaurant. Flagpole editor Pete McCommons previewed the performance, as seen below. As he says, the Pinecrest Lodge is “the place where it all began” for the Jesters.

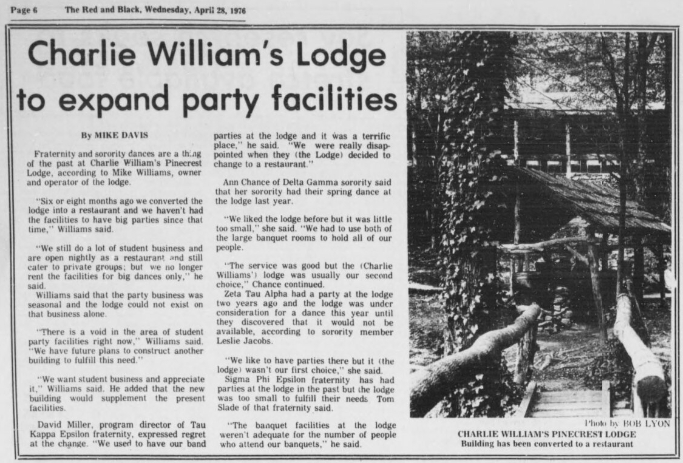

The modern era of the Pinecrest Lodge began in 1975, when according to the following Red and Black article the business switched from being a space for rent to a restaurant regularly open to the public. The article explains that as the University’s fraternities and sororities grew in membership, the facilities at the Lodge did not always prove to be sufficient. And the Lodge, in turn, wanted more regular business.

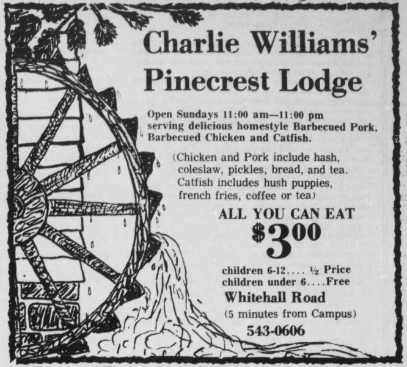

The advertisement below, from April, 1975, suggests that the transition to a restaurant had taken place by then.

In a Red and Black ad from 1977, the restaurant continued to try to allure student customers, hungry “after a long day at school.”

By 1983, the cost had risen from the three dollars it had been in 1975 all the way up to $5.95. Stagflation?

A 1993 Red and Black ad shows that the restaurant at that point gave customers two options for its buffet, the “Country Style” and the “Steak & Seafood.”

The restaurant expanded its options for customers in other ways. One was by offering take-out. The menu shown below likely dates from the 1980s or later, given the presence of Diet Coke, which debuted in 1982.

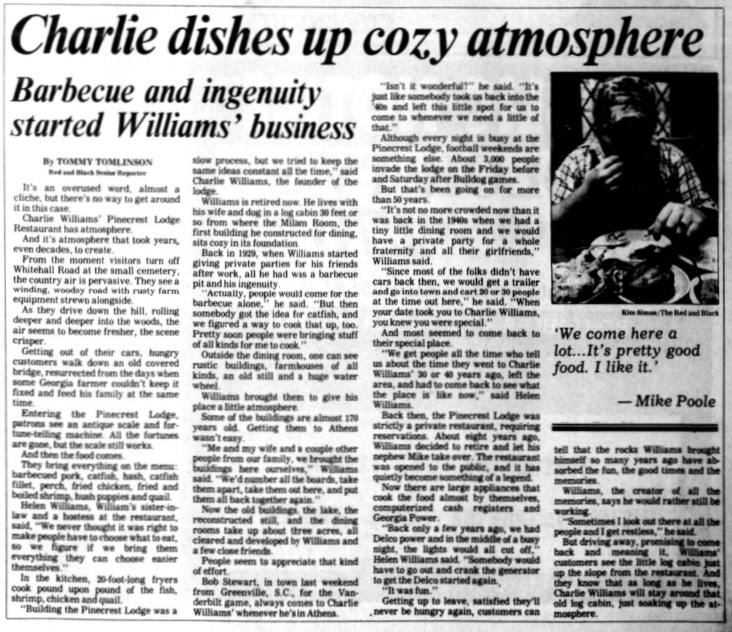

A 1984 article from the Red and Black captures what it was like to go to the restaurant. It notes the smaller buildings and other fixtures on the property, brought there by Charlie Williams and restored; these, combined with the water wheel and large dining rooms, helped create a traditional, home-cooked feel to the dining experience, even if it did count as “going out to eat.” Also of note is that former Athenians, coming to town for football games or other occasions, would flock to the restaurant.

Beginning at the latest in 1995, a second, smaller location, called Charlie Williams’ Pinecrest to Go, opened at 2020 Timothy Road (in a building that has since been replaced by the westside location of Loco’s).

The Pinecrest Lodge closed rather suddenly in early 2004, with the sale of the property. As noted above, another restaurant operated there for a short time, and Pinecrest to Go stayed open after the Lodge closed. Soon enough, though, the whole operation had became part of the city’s past. In the late 2000s, residents renting the waterwheel house held parties that featured local artists, keeping alive the tradition of live music on the Pinecrest property.

More recently, Mike Williams passed away, as reported by the Athens Banner-Herald.

As with our article on Rocky’s and and its eccentric proprietor, Bob Russo, we end with a few items from the Heritage Room Vertical Files. (The take-out menu shown above is also from these files.) These artifacts have been digitized at a high resolution. As with the clippings above, you can open these in separate tabs to view the full-sized versions.

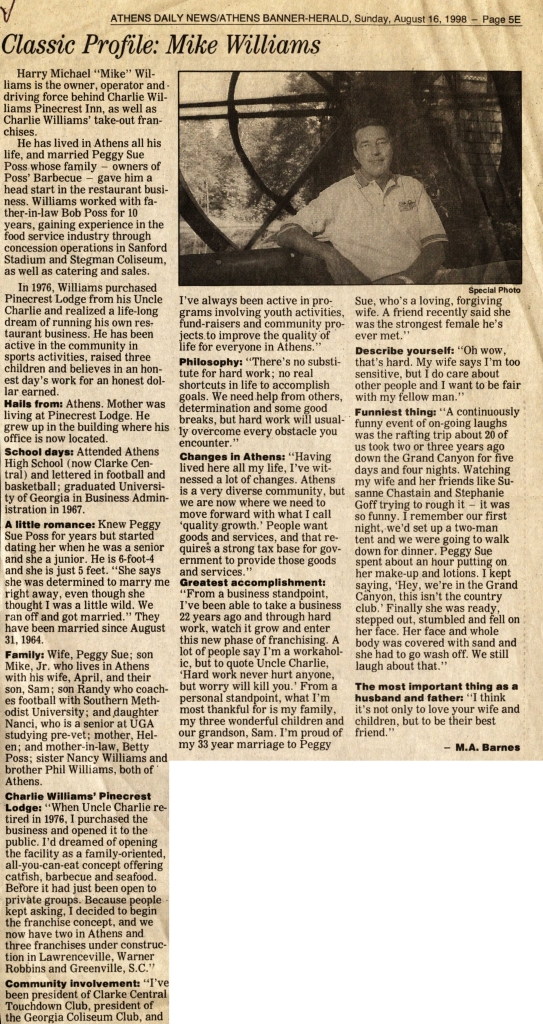

First up is a newspaper clipping. In this 1998 Athens Daily News/Athens Banner-Herald profile of Mike Williams, we learn more about him and his family and hear some of his observations about life and Athens.

Up next are three brochures, the first of which below shows both Charlie and Mike; it notes that Mike is the owner, suggesting this document dates from the late 1970s.

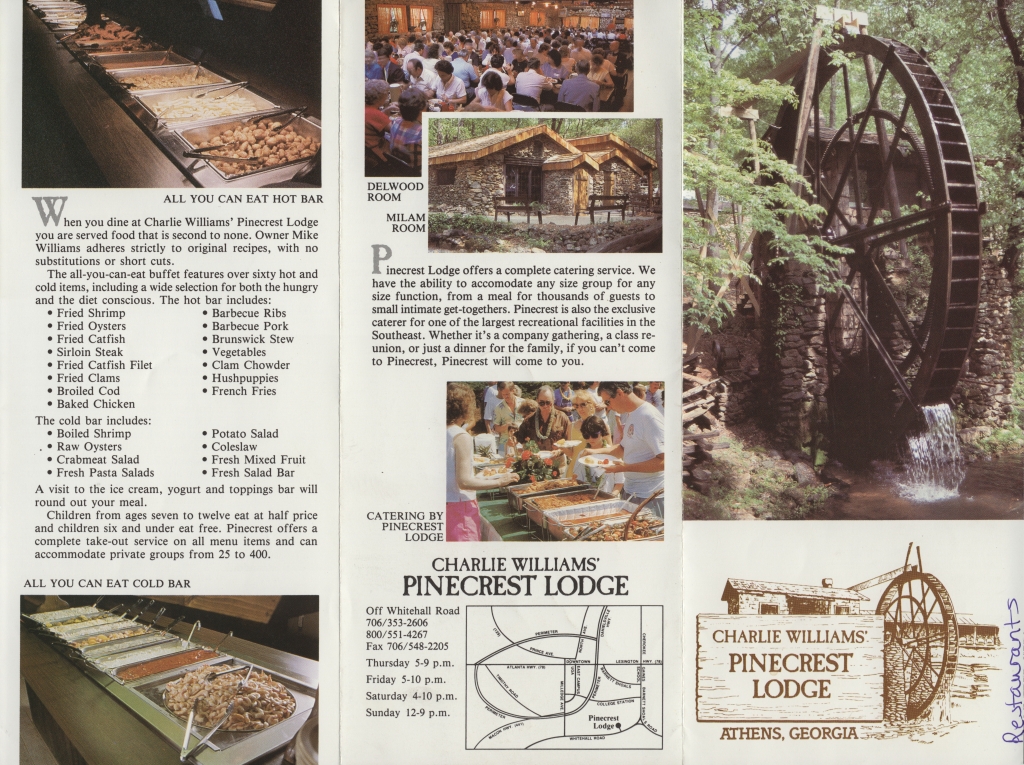

The colorful brochures seen below obviously came later.

A second version of this brochure used a couple different pictures. Besides the water wheel, these brochures identify a covered wagon, a liquor still, a sharecropper’s house, a fountain, and a blacksmith shop. These structures as well as the multiple dining rooms, and all of the memories and artifacts of the meals and parties held there, together create an Athens institution.