For now at least, the historical record of the Hodgson Oil building after the Buckhead Beach nightclub closed gets choppy. Although tax records give the names of persons or companies that owned the building, details regarding what went on inside have to be gleaned from newspapers. We get our first clue from the January 14th, 1987 Red and Black: an advertisement for the Athens Institute of Karate. No address given, it’s “at the old Buckhead Beach”—the readers knew where that was.

Five years later, the Flagpole published on May 13th, 1992 includes a note about a new club, Diva’s Dance. A few other notices from Flagpole later that year confirm that at least a few events took place there, but beyond 1992 the references to Diva’s are in the past tense. A mailing address is also found in this clipping, a rare occurrence in Buckhead Beach’s informal later years.

In the March 10th, 1998, issue of the Red and Black, we learn about perhaps the strangest use of the Buckhead Beach building. Sure it’s large, it’s a former warehouse with cavernous interior spaces (at the time, if not any longer). But a skateboard park? Inside? Alas, those who lived in Athens at the time likely remember the drawn-out controversy over skateboarders using empty lots at the corner of Pulaski Street and Hancock Avenue (later, two office buildings filled in the space). Studio E, as this new skate park was called, was meant to solve that problem.

The Flagpole for May 27, 1998 follows up on this story. A skateboarding facility entailed too many individuals being in the building at the same time; the fire marshal shut it down. As the article notes, bands were using Buckhead Beach as rehearsal space and parties were taking place. The former use did not present safety concerns and was common enough. In fact, in this author’s personal experience, I first became aware of goings-on at the building because I knew musicians who practised there.

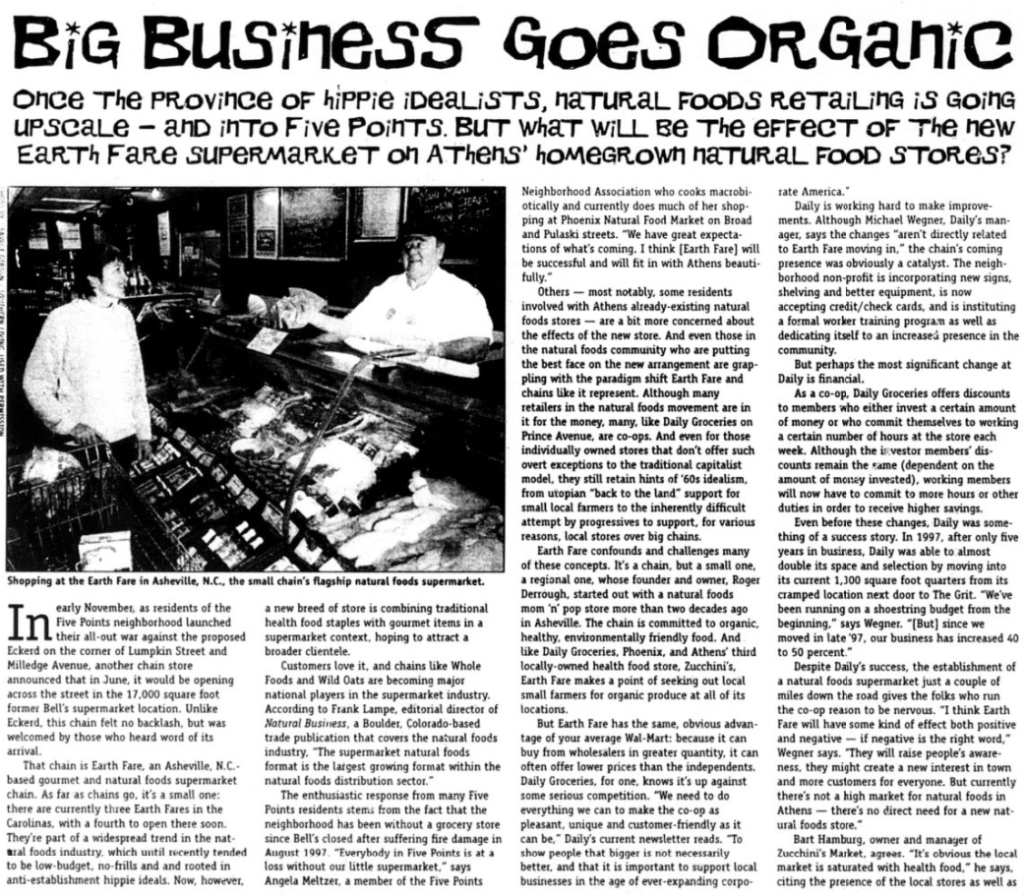

Buckhead Beach as a venue for live music, however, did present safety concerns. Unsurprisingly, the December 15, 1999, issue of Flagpole, as seen below, mentions a concert supposed to be held at Buckhead Beach that was shut down by local authorities. The promoters moved the show to House of Joe (the short-lived successor to the original location of Jittery Joe’s, in a space later occupied by the bars Engine Room and, later still, Max Canada; as seen in the image, the same column notes that another Jittery Joe’s located on Prince Avenue, where the Healing Arts Centre is now located, would soon close). This performance, though it did not end up happening at Buckhead Beach, provides a fine example of the kind of events taking place there in these years: unofficial, yet at times featuring artists of national renown who for the most part played proper nightclubs and theaters. The article also serves as a secondary source confirming that this Buckhead Beach was in the same building that housed the B & L Warehouse. (It also suggests that Athenians may have still called the building the B & L Warehouse instead of Buckhead Beach.)

Another memory of mine from that time is of reading about a pirate radio station in Athens. An article in Flagpole understandably did not give the station’s address. The station did not last long, shut down by governmental authorities. For years to come, I wondered where it had been located, but did not give the matter much thought. More recently, I talked with one of the persons who ran the station, someone I had known for some time without being told he had been involved. He confirmed for me the station’s location at Buckhead Beach. However, unless someone were to interview this person or others involved and thus create primary documents–that is, sources for other researchers to draw upon–such information remains hearsay. Where else is the illicit broadcasting operation mentioned?

In a Flagpole column earlier that year (March 17th, 1999) shown above, William Orten Carlton (“Ort”), Athens’ beloved record-store owner (Ort’s Oldies), raconteur, and newspaper columnist, provides a clue, stating that the station “broadcast out of a building on Oconee Street.” Our intrepid proverbial researcher, however, wants to confirm as well as possible that the pirate radio station operated out of the same building that once housed the Buckhead Beach nightclub and, before that, the “i and i club” and the B & L Warehouse. This clue is not specific enough.

A retrospective article about a local Athens band (Flagpole, December 6th, 2006) provides first-hand account of the activities that took place in the building toward the end of the 1990s. A primary source, a local musician involved in Spaceball Entertainment, the loose outfit that ran the rehearsal spaces and performance venue, confirms the location of the pirate radio station. He states plainly, Buckhead Beach was “where that pirate radio station was.” A secondary source, the author of the piece, further aids our inquiry, noting in passing that the “aging Hodgson Oil warehouse” and Buckhead Beach were one and the same.

While more details may await us in the microfilmed Athens Banner-Herald and Daily News, as well as the Athens Observer (up to the early 1990s at least), nonetheless we see clearly here how historical research, when it turns from public affairs to social happenings more private in nature depends more upon first-hand accounts: diaries, correspondence, interviews, memoirs, photographs, and so on. A recent book about Athens music, Grace Elizabeth Hale’s Cool Town, does not cover the late 1990s, but what will similar, future books about Athens or specific musicians who worked here have to say about Buckhead Beach? What sources will their authors turn to?

To bring this particular version of the Buckhead Beach story to an end, we turn to the April 29th, 2003 issue of the Red and Black, which bared on its front page a photograph of renovations taking place at what became the Hodgson Oil Building, the accompanying note letting us know of a couple other businesses that had been located in the building, perhaps around the same time as the karate school.

—Justin J. Kau